Where are the Women?

International Women’s Day celebrates the achievements of women the world over. It also serves as a reminder of how far we have to go to achieve gender equality. As a profession dominated by men, crewing in the UK has a gender problem. Anya Lawrence-Craig explores what is being done to bring about lasting change.

If you told Daniela Fleckenstein five years ago that she would essentially be working as a manual labourer, she would have laughed out loud. If you told her that she would be at one of the happiest points in her career, in her forties, unloading trucks and lifting heavy stages she likely would have laughed a little louder. A freelance photographer and creative specialising in theatre and costume production, Daniela had become disillusioned with the reality of her working day. “I had personal issues with being stuck in an office behind a computer,” she says. “I went freelance to get away from that.”

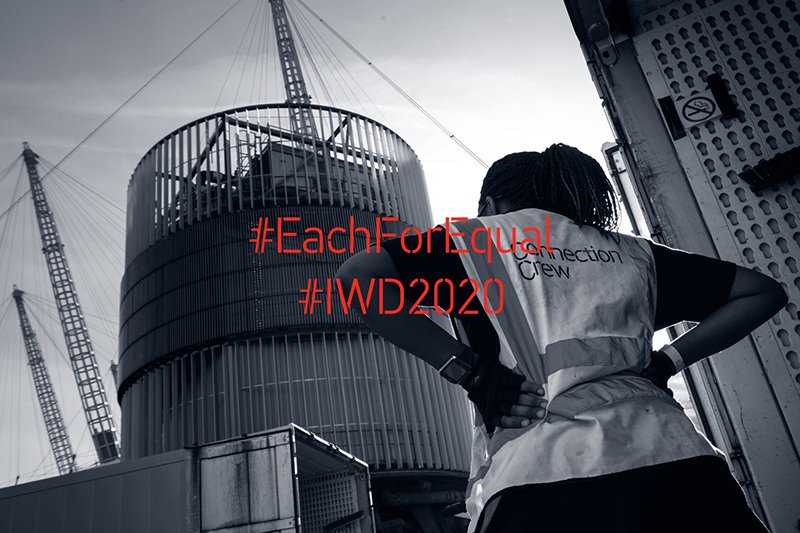

Daniela decided enough was enough; something had to change. It was around this time that she came across Connection Crew and was promptly propelled into the world of crewing. She has not looked back since. “I was surprised by the joy it brings to be physically active,” she says. “To quite literally, move and lift and make things happen. You get a very immediate satisfaction which is something that is hard to find as a freelancer or in other fields of work.”

The solitary aspect of life as a freelance creative was challenging for Daniela. “I like being around people,” she says. “I have discovered how important it is for me to work with others.” As a member of crew, working well as part of a team is crucial. “We are very close: you have to be,” she says. “The reason we work so well together is that we ‘get’ each other. We all come together and, almost instinctively, know what we are doing.” Rachel Stringer, a freelance Events Production Manager, agrees that the team element is one of the main draws of working on site in events production: “Generally you are all of the same mindset – you want to get something good done, in the best way possible, and you also want to have fun.”

For all that Daniela coos about crewing and her love for the job, the odds of her ending up in such a career are against her. Crewing in the UK is dominated by men; the few women that do crew are the exception. There is, however, little official data to quantify the extent of the gender imbalance in the crewing profession.

“It was a boys’ club … Even when working as festival crew [a sector considered more gender balanced], I’d often be the only female on site.” Fast forward 15 years and while production management appears to have progressed, crewing is still dominated by men.

When Rachel began her career 15 years ago the gender imbalance was critical. “It was a boys’ club,” she says. “Even when working as festival crew [a sector considered more gender balanced], I’d often be the only female on site.” Fast forward 15 years and while production management appears to have progressed, crewing is still dominated by men. “It is important to distinguish crewing from the rest of the industry,” notes Charlie Dorman, Co-Director of Connection Crew. “The rest of the industry has a much healthier gender balance – you see a lot of women in senior roles and lead technical roles – but crewing is still very much male-orientated.”

It was not something that Daniela had considered until she attended her first group interview. “It only dawned on me when I walked into the room that I was the only woman,” she says. “It was daunting. I thought ‘What have I let myself in for?’” Connection Crew actively welcomes women into its crewing teams and is making steps to attract and recruit a more diverse workforce. Preconceptions about crewing, however, often deter women from applying. As recently as January 2020, Connection Crew held the third iteration of its Employment Programme, a six-day training scheme, aimed at preparing those who have experienced or are at risk of homelessness for employment, particularly as crew. “In my communications, I made a point in saying that the programme is open to all genders,” says Alice Adams, an Impact Officer at Connection Crew who is responsible for running the programme. “I had 25 people sign up but there was only one woman.”

The very essence of crewing is perhaps where the problem lies. “Crewing has always been seen as people who lift heavy things and that is the bottom line,” says Rachel. “It is about physicality.” As crew, no two days are the same. Crew are required at all hours – day and night – and in all situations, from a muddy field to a ballroom. Granted there are heavy objects that crew are required to lift but there are also learnt techniques that make doing so entirely possible. “It is quite often getting an event or show into a venue or getting the event equipment – the stage, the set – out of a venue,” says Daniela. “Generally, loading or unloading a truck, getting the heavy things into a space and making sure things are where they need to be.”

“There is a bizarre stigma around women doing this work,” adds Charlie, who has over 20 years’ experience working on site at festivals including Green Man and Creamfields. “I think it comes from the idea that it is physical and heavy-duty work.” Daniela agrees: “It is probably down to the ingrained assumption that men are physically stronger than women. No more or no less than that. The funny thing about all these prejudices and assumptions is that they are so ingrained in society that you often believe it yourself.”

“Quite simply if we don’t have a diverse, gender equal workforce then we are not going to create strong female role models for women who have experienced homelessness to be able to thrive in our workforce,”

In reality the physical demands of crewing can be met by both men and women. “If you are doing anything that requires you to have a level of physical ability beyond what most women would be able to cope with, then either you are doing something really stupid and dangerous or you are doing it wrong,” says Charlie. “Yes, we do a lot of very physical work, and yes we often have very heavy objects to lift but there is a technique and we train that very carefully.”

Connection Crew is ardent in its ambition to make its crew more diverse. As a Community Interest Company (an organisation that aims to use its profits for good) that is committed to supporting and enabling people with a background in homelessness into employment, the organisation simply cannot do this adequately if its crew does not comprise both men and women. “Quite simply if we don’t have a diverse, gender equal workforce then we are not going to create strong female role models for women who have experienced homelessness to be able to thrive in our workforce,” says Charlie. “It would be extraordinarily naïve of us to believe that we could successfully employ women who have experienced homelessness in a very male dominated environment.”

But it is not straightforward. Connection Crew predominantly recruits its crew members through charities and services working directly with those at risk of, or who have experienced, homelessness. That in itself presents a problem. “The reality is that single men are often the largest group accessing homelessness services,” explains Alice, who has spent over five years working at homelessness charities including Crisis and Cardinal Hume Centre. “This is not to say that women are not homeless but they are not always as visible. They are much less likely to go out and sleep on the streets, instead, for example, they will sit on buses or A&E waiting rooms.” With women not accessing these services, it is difficult for Connection Crew to access them.

So what is Connection Crew doing to ensure its crew comprises a balance of both men and women? “It is difficult,” says Charlie. “We want to be recruiting people based on their ability to do the job and not positively discriminate.” Connection Crew focuses its efforts on visibility. Its branding is consciously neutral – and women and men equally feature in Connection Crew’s marketing. This makes all the difference. “When you are a minority,” says Rachel, “you don’t consider things that you don’t see other people like you doing.” When working with crew with a history of homelessness, Connection Crew is upfront about the challenges that arise. It embraces a flexible and, crucially, reactive approach. For Alice, this means involving crew with a background in homelessness in efforts to improve how Connection Crew supports its employees. “The best advice is from someone who has experienced it first hand,” she says.

Ensuring that there are female role models is also vital. “We have had some incredible Crew Chiefs who are women,” says Charlie. “You have to build that talent in-house. It takes time and there are few shortcuts, but it is something we really need to focus on. Those women become role models and are important components in successfully recruiting more women into our team.”

Ultimately, the number of female crew working in the UK will increase once society grasps the fact that strength is not an exclusively male trait, and when women have the self-assurance to put themselves forward for crewing roles. As a society we need to make it known that women are just as suited to labour-intensive professions as men. “For me it is about working as an equal,” says Daniela. “There are women that live by the assumption that they have to prove themselves [in a male-dominated workplace] and behave like the stereotype of men. But that is not right. You don’t have to be a hero or overcompensate because you are a woman, you just need to be yourself and good at your job.”

“Really,” adds Alice, “it has nothing to do with your gender. It is just a question of if you can do your job.”

If you are a crewing or event professional or someone representing women with lived experience of homelessness and would like to help Connection Crew on it’s aim to take action for equality, please do get in touch.

Contact Margarita Ktoris, Senior Communications Manager at margarita@connectioncrew.co.uk